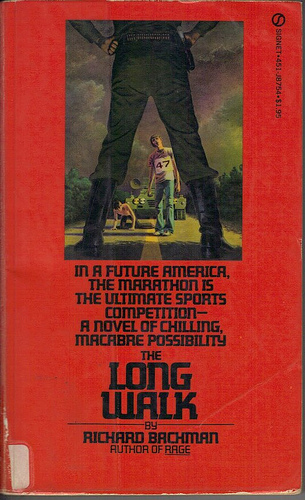

The Long Walk (Stephen King)

Pokud sledujete tyto stránky pravidelně, nemohlo vám uniknout, že se v oblasti knih a filmů velmi zajímám o soutěže, ve kterých jde účastníkům o život – viz např. kniha The Hunger Games (v češtině vyšla jako Aréna smrti) nebo film Slashers. The Long Walk od Stephena Kinga (česky vyšel jako Dlouhý pochod v roce 2005) také patří do této společnosti, a kdyby ničím jiným, tak zaujme tím, že jde o zřejmě nejstarší zpracování tématu vražedných soutěží. (Pokud znáte ještě starší, dejte mi vědět.)

Hned na počátku The Long Walk si všimnete jedné věci, kterou se kniha výrazně odlišuje od ostatních zástupců žánru: Vůbec se nezabývá uvedením čtenáře do situace, prostě ho postaví těsně před začátek soutěže a „starej se sám, člověče!“ King vám nic nedá na stříbrném podnosu, pokud vás zajímají pravidla hry, musíte si je poskládat z útržků poházených po celé knize.

Tedy ne že by šlo o kdovíco světoborného. Základní schéma se dozvíte velice rychle: Stovka mladíků z celé Ameriky se utká ve vytrvalostním závodě. Nejde v něm o rychlost, ale o výdrž – nezvítězí ten, kdo dojde nejdál, ale ten, kdo se vydrží pohybovat rychlostí aspoň 4 mil za hodinu nejdéle ze všech. Přitom není nijak zvlášť podstatné, jak bude toho pohybu dosaženo, klidně se můžete třeba plazit – ale jakmile vaše rychlost poklesne pod zmiňované 4 míle, dostanete varování a máte minutu na to, zrychlit opět nad stanovenou hranici. Jinak vás čeká druhé varování a pak třetí. Čtvrté už ne, místo čtvrtého varování přijde kulka do hlavy. Nikoho přitom nezajímá, proč rychlost klesla – že jde silnice do prudkého kopce nebo že zrovna spíte, to je váš problém.

Můj problém čtenáře je zase v tom, že nejpozději ke konci druhé kapitoly už je tohle všechno zřejmé a zatímco „závodníci“ začínají cítit únavu, ve mě začíná hlodat červík pochybností. Tak například, 4 míle za hodinu není zase tak úplně málo, když se to má udržovat dlouhodobě. Vážně mám věřit tomu, že to někdo zvládne čtyři nebo pět dní? I kdyby ten někdo byl výkvět Ameriky? A proč by vlastně člověk do takové soutěže lezl?

Velmi rychle vyvstane smyčka, ve které se děj knihy odehrává. Skupina závodníků celkem v pohodě postupuje a baví se o něčem ze své minulosti, co čtenáře seznámí s dalším z účastníků. Zhruba v okamžiku, kdy vyprávění dojde ke konci, začne mít některá z vedlejších postav problémy a za chvíli je po ní. A tak to jde pořád dokola, s tím, že zhruba každé druhé až třetí kolečko se týká někoho z hlavních hrdinů, u kterých se to liší jen v tom, že postiženému po třetím varování někdo pomůže a on může vesele pokračovat (a pak většinou následuje střih o tři hodiny do budoucnosti, kdy už má dotyčný zase „plný stav“ varování – po hodině se vždy jedno „odpáře“).

Můj hlavní problém s knihou je ale v něčem úplně jiném: King se velice důsledně vyhýbá všemu tomu, co v žánru zajímá mě – kde se soutěž vzala, jak funguje (třeba jak je financovaná nebo jak je chráněná před zákonem), jaký má smysl a jaké jsou v ní silné a slabé herní strategie. Nic z toho bohužel v The Long Walk zachyceno není; u té strategie to chápu, u velmi přímočaře nalajnovaného závodu, kde je tvrdě potlačováno jakékoliv (skoro jakékoliv – když se nejedná o hlavní postavu) fyzické vměšování do fungování ostatních, to dříve nebo později stejně spadne na náhodu. Ale doufal jsem v pozadí té hry samotné.

Faktem je, že jsem tuhle prázdnotu dlouho neprohlédnul. Autor totiž vůbec nešetří narážkami na nejrůznější okolnosti, které se soutěží souvisí, a ono to pořád vypadá, že se to celé nějak dá dohromady v konzistentní celek. Tady se musím omluvit za spoiler, ale bez něj by recenze nebyla kompletní – ono se to nikdy dohromady nedá. Kniha začíná se čtenářem plácajícím se uprostřed hluboké vody a také tam skončí. Narážky a náznaky navždy zůstanou právě jen narážkami a náznaky – matně na pozadí tušíme totalitu jako v Běžícím muži (The Running Man, také od Kinga, ale o pár let později), ale celý „Dlouhý pochod“ klidně může být úplně poctivá „demokratická“ soutěž, kde je zastřelení poražených prostě jen způsobem, jak povzbudit síly ostatních; indicie by pro to byly, počínaje plně dobrovolným vstupem do soutěže (včetně možnosti i na poslední chvíli odstoupit).

Jednu věc ovšem knížce nemůžu upřít: postupem času získává jakýsi hypnotický rytmus, který působí i navenek – skoro celou druhou polovinu jsem pociťoval únavu, jako kdybych ten závod šel sám, a posledních pár kapitol už jsem si čím dál důrazněji přál, ať mi sakra dají všichni pokoj a nechají mě v klidu umřít, to mají pocit, že jsem toho zatím vytrpěl málo?? Tímto se dodatečně omlouvám za některé své odpovědi zde na blogu, které bych za normálních okolností určitě neodbyl tak stručně…

Druhou stranou mince ovšem je, že třeba takové Battle Royale (Batoru Rowaiaru) od Koushuna Takamiho je ještě mnohem a mnohem sugestivnější – nenarazil jsem zatím na nikoho, kdo by film znal (knihu nezná skoro nikdo), kdo by nepřemýšlel o tom, jak by asi Battle Royale fungovalo v jeho škole. Nemluvě už o příšerně děsivém Sulphuric Acid (Amelie Nothomb), kde jenom doufám, že se ho nedožiju.

Jak na mě bude The Long Walk působit v dlouhodobém měřítku ukáže až čas, předběžně se ale nemohu zbavit dojmu, že to dopadne podobně jako s dalšími Kingovými knihami – na první přečtení to bylo OK, ale sotva kdy budu mít chuť se k nim vrátit – a když už to vlivem vzpomínkového optimismu udělám, tak rychle zjistím, že to fakt byl jen vzpomínkový optimismus a ne nedostatečné pochopení, když jsem byl ještě malý.

This is a great book. It was recommended to me by a customer who told me of all of King’s books, this one stayed with him the most. I only finished it yesterday but I can see that he’s probably right. I can’t really be within a group of people without somehow thinking we’re all like the boys in the Long Walk, trying to outdo everyone else as if our life depends on it. Yet, we’re trapped with one another, and the only thing that buffers us from insanity is other people (Sartre said hell is other people, but is lonliness really all that much better?) Well, not to get too philosophical or anything. It was a good, fast read. I was surprised most by the actual distance traveled in the Long Mile. I found myself wondering how they could still be on their feet, let alone walking at least 4 mph after hundreds of miles. And I was intrigued how desensitized the boys became to death, and how accepting they became of their own inevitable impending deaths. I can almost say some of them reached peace near the end. Perhaps that was the most disturbing part.The ending was vague, as many have said. But I think King made his point. The winner wasn’t really a winner after all.

Battle Royale jsem myslel specialne knihu, ktera je jeste o dost lepsi nez film (jednicka).

Battle Roayale znám, oba díly. Jednička super, dvojka tragédie. Napadlo mě, jestli by se do té Vaší kategorie soutěží o život dala klasifikovat válka? Pak by byl výběr asi dost široký:) Ještě tak trochu mimo téma mě napadl film inspirovaný skutečnou událostí – Přežít (Alive).

Z Nichollsovy encyklopedie SF. Signatura na konci znamena Brian Stableford/Peter Nicholls, proto jsem radeji upozornoval na prava.

Moc zajímavé info, děkuju. Budu se po těch jmenovaných věcech muset poohlédnout.

Zkusil jsem dohledat originální článek, ale Google kupodivu neuspěl. Odkud pochází ta citace?

Jeste jsem nasel tohle, ale nevim, jak je to s autorskymi pravy, takze klidne smazat.

This entry deals with games as a theme within sf. Games based on sf are treated under GAMES AND TOYS.

Just as sf’s concern with the ARTS has been dominated by stories about the decline of artistry in a mechanized mass society, so its concern with sports has been much involved with representing the decline of sportsmanship. There is a marked tendency in contemporary sf to assume that the audience-appeal of futuristic sports will be measured by their rendering of violence in terms of spectacle: the film ROLLERBALL (1975) is perhaps the clearest expression of this notion.

There are two forms of stereotyped competitive violence which are common in sf: the gladiatorial circus and the hunt. The arena is part of the standard apparatus of romances in the Edgar Rice BURROUGHS tradition, and extends throughout the history of sf to such modern variants as that found in the Dumarest series by E.C. TUBB (1967 onwards). Combat between human and ALIEN is the basis of Fredric BROWN’s popular „Arena“ (1944) and a host of similar stories, while many visions of a corrupt future society foresee the return of bloody games in the Roman tradition-Frederik POHL’s and C.M. KORNBLUTH’s Gladiator-at-Law (1955) is a notable example. The BattleTech SHARED-WORLD series (see also Robert THURSTON) moves the formula on to a galactic stage. Ordinary hunting is extrapolated to take in alien prey in such stories as the Gerry Carlyle series by Arthur K. BARNES (1937-46; coll 1956 as Interplanetary Hunter), and a familiar variant has mankind as the victim rather than the hunter; examples include THE SOUND OF HIS HORN (1952) by SARBAN, Come, Hunt an Earthman (1973) by Philip E. HIGH and many works by Robert SHECKLEY, ranging from „Seventh Victim“ (1953) and „The Prize of Peril“ (1958) to such recent novels as Victim Prime (1986 UK) and Hunter/Victim (1987 UK). A notable series of relevant theme anthologies is the 3-vol Starhunters series (1988-90) ed David A. DRAKE. The oft-presumed equivalence between the spectator-appeal of sport and that of dramatized violence reached its peak in Norman SPINRAD’s „The National Pastime“ (1973) and the film DEATH RACE 2000 (1975).

An opposing trend is one which suggests that the people of the future might substitute rule-bound war games for actual wars, thus avoiding large-scale slaughter of civilians. The idea was first mooted by George T. CHESNEY in The New Ordeal (1879); sf versions of it include „Mercenary“ (1962; exp vt Mercenary from Tomorrow 1968) and its sequel The Earth War (1963) by Mack REYNOLDS and the Gamester War series begun with The Alexandrian Ring (1987) by William R. FORSTCHEN, and also a number of films, including GLADIATORERNA (1968) and ROBOT JOX (1990).

The sf sports story is almost entirely a post-WWII phenomenon, although the pre-WWII pulps did feature Clifford D. SIMAK’s „Rule 18“ (1938) — in which one of the ever-popular „all-time great“ teams is actually assembled — and one or two rocket-racing stories, such as Lester DEL REY’s „Habit“ (1939); and much earlier van Tassel SUTPHEN had included a couple of golfing-sf stories in his The Nineteenth Hole: Second Series (coll 1901). Many early post-WWII stories are accounts of man/machine confrontation (> MACHINES; ROBOTS). Examples include the golf story „Open Warfare“ (1954) by James E. GUNN, the boxing stories „Title Fight“ (1956) by William Campbell Gault and „Steel“ (1956) by Richard MATHESON, the chess story „The 64-Square Madhouse“ (1962) by Fritz LEIBER, and the motor-racing story „The Ultimate Racer“ (1964) by Gary Wright, who also wrote a fine bobsled-racing sf story in „Mirror of Ice“ (1967). The changing role of the automobile in post-WWII society provoked a number of bizarre extrapolations, including H. Chandler ELLIOTT’s violent „A Day on Death Highway“ (1963), Roger ZELAZNY’s story about a car-fighting matador, „Auto-da-Fe“ (1967), and Harlan ELLISON’s „Along the Scenic Route“ (1969). Other popular sf themes are often combined with sf sports stories. Gambling of various kinds appears in many ESP stories, for obvious reasons, and superhuman powers are occasionally employed on the sports field, as in Irwin Shaw’s „Whispers in Bedlam“ (1973) and George Alec EFFINGER’s „Naked to the Invisible Eye“ (1975). Stories which examine the possible impact of biotechnology on future sports include Howard V. Hendrix’s „The Farm System“ (1988) and Ian MCDONALD’s „Winning“ (1990). Full-length novels about future sport are relatively rare; examples include The Mind-Riders (1976) by Brian M. STABLEFORD, about boxing, and The New Atoms Bombshell (1980) by Robert Browne (Marvin Karlins [1941- ]), about baseball.

Games are used as a key to social advancement and control in a number of stories, including The Heads of Cerberus (1919; 1952) by Francis STEVENS, World out of Mind (1953) by J.T. MCINTOSH, SOLAR LOTTERY (1955; vt World of Chance) by Philip K. DICK and Cosmic Checkmate (1962) by Katherine MACLEAN and Charles V. DE VET. Some sf stories produce future or alternate worlds where games are fundamental to the social fabric, as in Hermann HESSE’s Das Glasperlenspiel (1943; trans M. Savill as Magister Ludi 1949 US; preferred trans Richard and Clara Winston as The Glass Bead Game 1969 US) and Gerald MURNANE’s The Plains (1982); a vicious games-based culture is successfully attacked by the protagonist of Iain M. BANKS’s space opera The Player of Games (1988). In other novels by Philip K. Dick, including The Game-Players of Titan (1963) and THE THREE STIGMATA OF PALMER ELDRITCH (1965), games function as levels of pseudo-reality. Sf writers who have shown a particular and continuing interest in games or sports include Barry N. MALZBERG, who often uses surreal games to symbolize frustrating and ultimately unbeatable alienating forces — as in the apocalyptic Overlay (1972) and Tactics of Conquest (1974), and in the quasi-allegorical The Gamesman (1975) — George Alec EFFINGER, who also uses game situations as symbols of the limitations of rationality and freedom, notably in „Lydectes: On the Nature of Sport“ (1975) and „25 Crunch Split Right on Two“ (1975), and Piers ANTHONY, who often uses games to reflect the structures of his plots, notably in MACROSCOPE (1969), Ox (1976), Steppe (1976) and Ghost (1988). The game which has most frequently fascinated sf writers is chess, featured in Charles L. HARNESS’s „The Chessplayers“ (1953) and Poul ANDERSON’s „The Immortal Game“ (1954) as well as Malzberg’s Tactics of Conquest. John BRUNNER’s The Squares of the City (1965) has a plot based on a real chess game, and Ian WATSON’s Queenmagic, Kingmagic (1986) includes a world structured as one (as well as worlds structured according to other games, including Snakes and Ladders!). Gerard KLEIN built the mystique of the game into Starmaster’s Gambit (1958; trans 1973). A version of chess crops up in the work of Edgar Rice Burroughs — in The Chessmen of Mars (1922) — and a rather more exotic variant plays an important role in The Fairy Chessmen (1951; vt Chessboard Planet; vt The Far Reality) by Lewis Padgett (Henry KUTTNER and C.L. MOORE). An anthology of chess stories is Pawn to Infinity (anth 1982) ed Fred SABERHAGEN.

In recent years the rapid real-world evolution of electronic arcade games and home-computer games has sparked off a boom in stories where such games become too real for comfort. Notable examples include „Dogfight“ (1985) by Michael SWANWICK and William GIBSON, Octagon (1981) by Saberhagen, TRUE NAMES (1981; 1984) by Vernor VINGE, ENDER’S GAME (1978; exp 1985) by Orson Scott CARD, God Game (1986) by Andrew M. GREELEY and Only You Can Save Mankind (1992) by Terry PRATCHETT (see also VIRTUAL REALITY). Stories of space battles whose protagonists are revealed in the last line to be icons in a computer-game „shoot ‚em up“ may have succeeded Shaggy God stories (> ADAM AND EVE) as the archetypal folly perpetrated by novice writers (although Fredric Brown’s similarly plotted „Recessional“ [1960], where the protagonists are chessmen, has been much anthologized). Many computer-game scenarios are, of course, sciencefictional, as are many of the scenarios used in fantasy role-playing games (> GAMES AND TOYS; GAME-WORLDS).

When it comes to inventing new games, sf writers have had very limited success. There have been one or two interesting descriptions of sports played in gravity-free conditions, but these are usually incidental to the real concerns of the stories in which they occur; stories set in SPACE HABITATS frequently include descriptions of „flying“ games played in the vicinity of the rotational axis. Sling-gliding, in which glides are accelerated by massive steel whips, is a plausible and dangerous sport featured in The Jaws that Bite, the Claws that Catch (1975; vt The Girl with a Symphony in her Fingers) by Michael G. CONEY. The sport of hussade, which plays a major part in Jack VANCE’s Trullion: Alastor 2262 (1973), is unconvincing. The board-game vlet in Samuel R. DELANY’s Triton (1976) is cleverly presented, but the details of play are necessarily vague. This game was first written about by Joanna RUSS in „A Game of Vlet“ (1974).

Games and sports are also very common in FANTASY and SCIENCE FANTASY, especially that set in post-HOLOCAUST or primitive worlds, as in Piers Anthony’s early trilogy (1968-75) collected as Battle Circle (omni 1977), or Eclipse of the Kai * (1989) by Joe Dever and John Grant (> Paul BARNETT), which features vtovlry, a rugby analogue played triangularly and with throwing-axes. Indeed, the metaphoric nuances of games enliven fantasy of all sorts, from the croquet and card games in Lewis CARROLL’s Alice books to Sheri S. TEPPER’s True Game series; in both cases the arbitrary and obsessive nature of games-playing becomes an image of life itself.

A relevant theme anthology is Arena: Sports SF (anth 1976) ed Barry N. Malzberg and Ed FERMAN. [BS/PN]

See also: LEISURE

Vrazedne souteze je pekne tema. Nejstarsi, co me napada, jsou asi Sheckleyho Prize of Peril a Seventh Victim – nekolikrat zfilmovane. Co se filmu tyce, zalezi na tom, jak siroce se to pojme. Ze 70.let by tam daly zahrnout treba takove veci jako Punishment Park, Rollerbal nebo Mort en direct. Urcite je toho spousta.